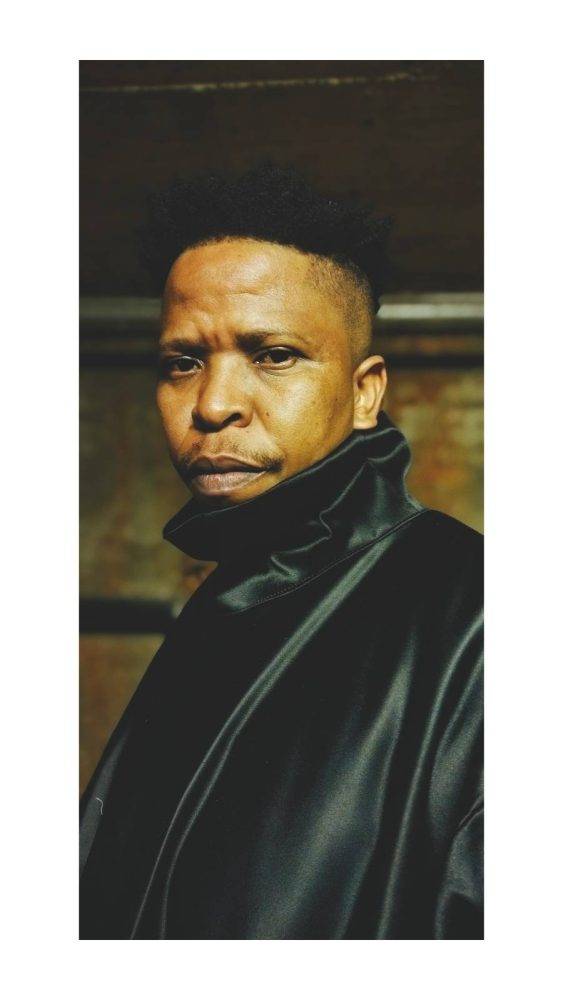

Siyabonga Mthembu: Musical prayers said by hymn-self

The self-described ‘performance artist who happens to sing’ speaks to us about his work

Siyabonga Mthembu is no ordinary vocalist. His capacity to invoke the worlds of the seen and unseen through a deliberately meditative pace and his ability to hasten us into urgency with exploding vocal riffs and repetitive plosives situate him well beyond the confinements of genre.

Mthembu invites us into prayer, action and revolution through his urgent prose and lyricism. Each note situates us in new worlds, new dimensions and new conceptions of our shared oral histories. Mthembu is indeed no ordinary vocalist.

He is often understood as the leader of the avant-garde, punk infused, jazz-adjacent band The Brother Moves On. In reality, he tells me, he is “not an artist or musician, but a performance artist who happens to sing”.

This is perhaps why Mthembu can flit effortlessly outside of the confines of genre. Bending his lyricism and vocal instrument to his will, he offers new aural possibilities imbued with the memories and the knowledge systems of the past.

“I have let go of jazz as a definition of what we do,” starts Mthembu, as we sit down in his new home. Earlier in the day, he had arrived back from a string of performances with his band in Cape Town. He is visibly tired, but despite his obvious exhaustion, he leads with a determined gentleness as he speaks to me, his wife and daughter listening.

“This weekend, I was telling some guy that the Americans can keep jazz,” he says in a matter-of-fact tone.

“The Americans can keep jazz because I think it’s like the idea of black power. We call ourselves black because of the trans-Atlantic but we are abantu abansundu.” (Black people, although the English translation doesn’t quite capture it.)

This is not tautology, but rather a radical invocation of humanism, as I understand it. What Mthembu is pointing to in this distinction is a set of principles that implicate us all in the idea of being human.

In his idiosyncratic way, Mthembu develops compositions and poetry by incorporating South African jazz, rock and funk to demonstrate what it means to be “rhythmically South African” — African and of the world.

He eschews the imperial categorisation of jazz as the music of the Americas and the music of African and indigenous folk everywhere else as part of that other, nondescript, “world music” category.

Being a prolific international figure himself, or rather “Hymn-self” as his solo moniker suggests, he has had time to reckon with these ideas both critically and artistically.

Mthembu is also the lead singer of Shabaka and the Ancestors. His solo work has featured at the Venice Biennale (2021), The Gwangju Biennale in South Korea (2020) and at the Sao Paulo, Brazil Biennale (2023).

He has performed on stages alongside adventurous artists and outfits such as The Metropole Orchestra, Tumi Mogorosi, Nubya Garcia, Hugh Masekela, Thundercat, Madala Kunene, Tshepo Tshola, Thandi Ntuli and Bokani Dyer, to name a few.

He also brought with him a searing re-interpretation of Zim Nqgawana’s A Long Waltz to Freedom.

Most recently, Mthembu performed at the Delicious Music Festival, where he paid tribute to the South African luminary reggae artist Lucky Dube. In the days before and after, he questioned why he, specifically, was assigned the responsibility of raising Dube’s ghost.

“The Uber that I caught to Cape Town was driven by Lucky Dube’s backing singer. The guy I met at the airport when I landed was one of the guys who toured with Lucky Dube.

“So, going from not really knowing a lot about his music, to having an audience member coming up to me after the show and saying that they had closed their eyes and could hear Dube, reminded me part of the journeying is within the actual music.”

This story, which Mthembu narrates so tenderly, is proof of a universe conspiring to imbue the figures of the past with contemporary expressions of the new.

A few days before this, he performed chapter two of a South African symphonic jazz songbook at the Linder Auditorium with The ZAR Jazz Orchestra, which is comprised of various acclaimed jazz musicians.

This time, Mthembu brought the late Hugh Masekela into the room, along with a reinterpretation of iconic jazz exiles Johnny Dyani and Mongezi Feza in the Dear Africa arrangement orchestrated by Marcus Wyatt.

His re-imagining of these figures shifted the room with its poetic urgency. Each rendition was punctuated by his majestic vibrato and the clinical precision of his storytelling.

Part of the success of Mthembu’s storytelling was due to the poignant poetry in the liner notes of the Shabaka and The Ancestors album titled Wisdom of the Elders.

Written by Lindokuhle Nkosi, the notes start off simply: “In the burning of the Republic, it is always the flattened mountain that performs the first act of self-immolation. Then the shacks (too close, a mouth with too many teeth jostling for attention) in protest of their own impoverishment.”

These words, for all intents and purposes frame the life-world of We Are Sent By History, but also frame the real worlds and words inscribed into those who live in places such as Palestine, Haiti, Sudan and the Congo. These words are also eerily familiar to many South Africans who are outside of the material bounds of citizenship, despite being born here.

At the Linder Auditorium, Mthembu borrowed from Nkosi’s liner notes by repeating the refrain, “We need new names, we need new psalms.” The refrain soon became a prayer and an invitation for the audience and the musicians to commune with each other and with spirit.

“I like prayer to be lived,” Mthembu explains as he reflects on this moment. “We have the private prayer spot but, as a black family, we always pray together. As The Brother [Moves On band], every time we get onto stage, we hold each other and pray. My grandfather was a bishop. Whenever he was leaving home, we would all have to come into the kitchen to say a prayer.

“I feel that, because he was able to make it such an embodied thing for me, similar also to my mother, that I don’t need for it to be a Christian [prayer],” he continues.

Mthembu wrote on social media about the Indaba Is album, which he co-produced and co-curated with pianist and composer Thandi Ntuli: “Theirs is a communal effort continued from our elders who are passing without the proper recognition. The children have heard Indaba, uthixo ukhona [God is with us].”

In the weeks to come, Mthembu will co-curate a concert series with Ntuli titled Sikelela at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg.

As the press release reads, taking its cue from the word “sikelela” meaning “blessing”, from the first phrase in the South African national anthem, this event celebrates a tradition of Ingoma (sonic meeting place) as a practice in the intimate exercise of liberation in action.

This special concert invites visionaries from the avant-garde of the South African jazz and live music scene. Sikelela celebrates the tradition of Ingoma in the intimate exercise of liberation in action.

Sikelela, which takes place on 19 October, will include Ntuli, pianist and composer Keenan Meyer, folk singer Muneyi and The Brother Moves On. The second iteration of this concert will be at the Barbican Theatre in London featuring Thandiswa Mazwai, Ntuli, Mogorosi, Meyer, Dyer and The Brother Moves On, plus British musicians, Soweto Kinch and Chelsea Carmichael.

Perhaps, said differently, Mthembu is co-curating another set of musical happenings where prayer can be reinscribed into a tool of justice, empathy and new-world building.

What's Your Reaction?