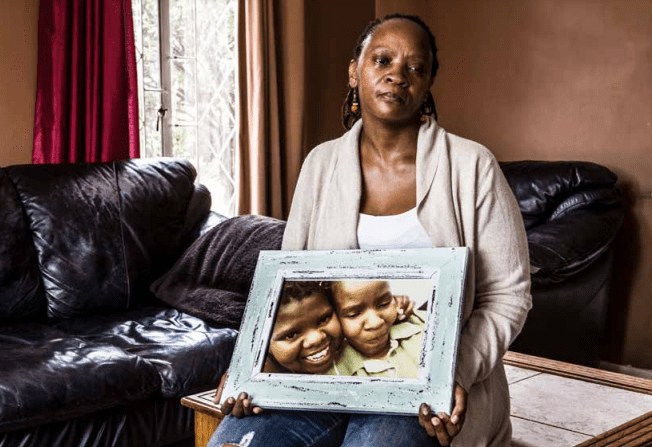

Excerpt: The Story I Told Myself

An edited excerpt from the historical novel by South African author Arvashni Seeripat

(Contains descriptions of graphic violence)

I couldn’t remember the last time I felt this safe — tightly rocked in warm embraces and softly lulled to sleep. I wanted to stay like this forever. The warmth was tempting me with a forever sleep.

I wanted to close my eyes and stay tucked away in this corner of the floor for all my days. But that feeling was interrupted by a sticky dampness that rolled down my neck, burrowing itself into the opening in my blouse and making a pool under my breast. I watched the blood quizzically.

Where was it coming from? Certainly not my body? I couldn’t feel anything. My blouse couldn’t contain the pool, and the blood seeped through the fabric.

The embrace was warm, and yet it moved. It became more urgent.

“Mama, open your eyes. Mama! Please!” Uma’s tiny arms squeezed me awake. Her high-pitched six-year-old voice led me back to her. Why was Uma waking me? We were all sleeping on the train. We were safe.

“Uma? Why are you waking me? Sleep child, you must rest.”

“You are bleeding, Mama! Please, Mama. Look at you!”

Except we were not on the train now. I was in yesterday afternoon’s nightmare, reliving each moment with my children. I could hear Uma’s sobs locked within a whisper in case my husband heard and knew I was awake.

If he thought I was alive, the pain would start all over again. Uma’s cries were like the spaces between words, blank; but without them, no meaning could be communicated. She spoke to me in those whispered sobs between words.

I was barely alive, but alive. My opened eyes were covered by the haze of the midday sun. There was fire in my mouth, and it burned hot, burned blue. My nose was wobbly. I knew it was dislodged from its place.

I blinked rapidly to clear the haze and saw pearls lying on the floor, glistening in the sun. The discoloured whites mixed with the dust and blood. The purity of the whites was painted by the filth around it, tainted forever.

The back of my hand reached out to wipe out the fire in my mouth. And then I realised in growing horror that the pearls on the floor were my front teeth, lying like a broken necklace waiting to be crushed under a careless foot.

My teeth were not the only broken tokens on the floor. The crescent half-moon of my bangles made a tangled pattern strewn across the dust. Red and green coloured the floor in a way that I had never been allowed to own colour in my life.

I could feel tiny erratic quivers coming from beneath me. Hari quietly shivered as he hid buried under me. My arm ached terribly but not enough to stop me from lifting it to check on Hari. My baby boy’s beautiful eye was swollen shut.

The angry red colours were a sign of danger, and for years, no one had seen or listened to these signs that flashed everywhere we turned. Today, in the dusty golden glow of sunlight, this little boy, whose only indiscretion was to be born my child of this man, hid in my sari folds. Hari often paid the toll of his birth with his body and spirit.

No one escaped this man’s madness. Not even his blood. The anger and the fists got worse every day. To the world, we were his family. To him, we were the bodies he owned, and he used us to appease his anger every day.

Very early on in our marriage, I learned that my blood would be sacrificed to his fists. I didn’t know that if I were not enough, anyone within reach would suffice, including his children.

As I tried to pull Hari out from under me, Uma helped me. Hari refused to show his face to the world. My child hid his face and hoped that his life was small enough so that no one noticed him.

He burrowed into me; his one normal eye wide with fear. The darkened patch of his swollen eye shadowed the despair in my heart. My sari was no protection for Hari’s fragile body, and my body was no shield against him if he reached for Hari again.

Uma saw my pain and held my hand, creating a bridge for my broken soul. Uma and I were twin bridges that arched over a history of tears and a river of blood. Her hand was hardened and rough. When had it become so rough?

While her one hand built a bridge, the other held an old steel knife. It was dark with age and had seen life beyond us […].

“Uma, where did you get this from?!” I was angry and thankful.

“I took it from under Dadi’s (her paternal grandmother’s) carpet when she asked me to clean her room. Don’t be mad, Mama. Please don’t be mad. I took it because we needed something to help us. No one helps us. Everyone just watches him hurt you.”

I couldn’t argue. Her innocence and honesty were hard to refute.

“Mama, please take it. Please. You need to take it now,” Uma whispered urgently through her tears. “I am scared. What if he comes back?”

We all feared him even more because he was this way stone-cold sober. This man had anger in his veins, and cruelty was his lifeblood.

Tainted pearly moons called out to me in my own voice. “Now, Shivali. Take it. And if he comes at you again, finish this before it is more than your teeth and your blood. Before Uma’s and Hari’s become the next spirits and bodies he injures.”

Our shuffling and whispering awakened the beast, and he burst into the room. I smelled his rotten breath as he exhaled on my face. I knew that a blood sacrifice would happen here today.

He aimed a punch at my ear, but I knew that he was coming this time, so he only managed to graze me. The ringing made me sway wildly, even in my seated position. But this same position gave me an open view of his neck.

He swung with so much force that he stumbled forward, bringing him closer to me. I plunged the knife into his fleshy neck over and over. It was surprising how soft his neck was. The beast would be so thrilled to see how much was spilled.

Blood shot from his vein and hit the walls like a jubilant offering. The same veins that carried his cruelty sprayed his evil all over the walls. Blood covered the twinkling of pearls and moons.

He collapsed in front of us without a word. I had killed him. His blood covered everything—the walls, the floor, and me. It glued my hair together and soaked my clothes.

As I lifted my hand to wipe the blood off my hair, I realised that I had the knife in that hand. It now wore not just his blood, but my sindoor (a traditional vermilion red powder used as a symbol of marriage for Hindu women) too. I thought the children had escaped him, but the look of abject horror on Hari’s face told a different story.

“Hari, Uma, we have to get out of here before anyone sees us.” The children didn’t even drop a tear of sorrow for this man that fathered them. Too many tears of pain had been shed throughout the years.

“But you have blood on your face and clothes, Mama. You have to wash that off first and change your sari. Let me get you some water. Stay here.”

Before I could even respond, Uma was out the door. This six-year-old was too old to be a child. While she went for water, I grabbed the only thing of value besides my children, my Ramayana (Holy Book of Ram) from its hiding place at the back of the cupboard.

This book that brought me solace and my children were the only things to call my own. The thud of the train stop brought me out of my nightmare. We stopped at another village. […] The sun was much higher in the morning sky now. This station was much busier than Dwarpur, and the food sellers were in full sight. I sat up with the previous day’s images still in my mind and the feeling of the wind behind us as we ran to the temple. That was the only place I could think of going to.

The safety of the temple was what we needed, even if it was just for one night. I could still feel the slap of the metal blade against my breast, peeking from its place in my blouse.

The Story I Told Myself is distributed by Praxis.

What's Your Reaction?