The sculptures where nothing is true and everything is permitted

Recent shows by the sculptors Nolan Oswald Dennis, Vusumzi Nkomo and Diana Vives make for fascinating viewing

Among the exceptional, singular and, yes, occasionally awful, artworks in the permanent collection of the South African National Gallery, one work stands out as truly enigmatic. It is an untitled paper installation principally composed of repurposed cement packaging that Moshekwa Langa found on the streets of KwaMhlanga, the short-lived capital of the KwaNdebele homeland, shortly after finishing high school in 1993.

This canonical work appears on the must-see exhibition surveying Langa’s category-resistant practice at A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town. Titled How to Make a Book, it declares its purpose — there is an in-depth publication on the artist in the works.

The works on show at A4 span the period 1995 to 2018. There are a half-dozen pieces from the 1990s, when Langa emerged — self-taught, fully formed and fax-enabled — on the local art scene. They include Dor, a speculative flag made for a 1998 exhibition in Rotterdam, Holland, as well as his untitled paper installation from 1995.

Three wires running obliquely across the central gallery of A4 display about 20 unbleached fragments of irregularly shaped paper that Langa recycled from discarded cement packaging.

“First you invent the country; then, if you can, an economy,” wrote American journalist Joseph Lelyveld in 1985 of KwaNdebele, a proxy state being built in a hurry.

As late as 1994, when Langa was retooling his admiration of fellow artist Judith Mason into a personal practice, cement from Pretoria Portland Cement, one of South Africa’s oldest companies, founded in 1892, was being used to enact “separate development” — the euphemism for late-stage apartheid.

Sensing opportunity in the ersatz art material littering KwaMhlanga, he set about collecting and processing it. Langa treated the paper with chemical disinfectant, turpentine and creosote. In addition, he imprinted it with marks using homemade charcoal and candle wax.

Critic Hazel Friedman, reviewing Langa’s debut solo at the Market Theatre in 1995, honed in on the suspended cement bags. She likened them to animal hides.

A young Clive Kellner, who now heads up the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation in Forest Town, presciently wrote: “Langa provides a sense of the future.”

Emma Bedford, then a curator at the national gallery, shared Kellner’s optimism and pushed her institution to acquire Langa’s installation.

“I was convinced that it was an important work that belonged in the national collection,” Bedford told me in 2013, when I was researching this work for an unrealised book project.

Persuading others of the work’s merits proved tough.

“It took many meetings over many more months to convince my colleagues,” she recalled.

In the main, Langa’s work lives in boxes in storage, but here it is again, on public view, illuminated by a preposterous, but indisputable, designation: canonical. Joyfully, his work remains as enigmatic as ever, beyond the easy capture of words. Of course, this is just my opinion.

Subjectivity, an evergreen faction within the art world will tell you, is the only truth. Maybe. I prefer author William Burroughs’s mantra, which he borrowed from the 12th-century Islamic leader Hassan-i Sabbah: “Nothing is true. Everything is permitted.”

It offers a useful working thesis for negotiating the material facts and thrilling permissions taken, not only by Langa, but also Nolan Oswald Dennis, Vusumzi Nkomo and Diana Vives, artists who have made Cape Town an interesting place to view art over the past few months.

Of the bunch, Brazilian-born Vives is unquestionably the sculptor. Her recent exhibition at Everard Read’s Circa Gallery in Cape Town, The Fire in the Mind, included works made from various stones (Archaean greenstone, dolerite, Carrara marble) and wood (pin oak, pine, eucalyptus). Often the materials are presented as found or only minimally reworked.

Originally created for her master’s degree show last year, A Further Shore perfectly embodies the drifting, associative qualities that inform her best works. It comprises the remnants of a fire-scarred red river gum that Vives rescued from a rubble pile on the Cape Flats.

“Fire is not a thing, nor an element, but a process of transformation,” wrote Vives in the text accompanying her exhibition at Everard Read.

In and of itself, the wounded stump is only moderately interesting. Vives added 20 turned beechwood legs to it, each leg different in shape, and each fitted with brass piano castors. The resultant bipartite work is ungainly in proportions but somehow deeply moving.

By contrast, sculpture is an inadequate word for pinpointing what Nkomo and Dennis do as artists.

Take Nkomo, who made a big splash this year with two solo exhibitions in quick succession.

In July, Nkomo — a university-trained journalist who in 2021 enrolled in a fine art degree at the Cape Town Creative Academy, where he now teaches — presented his debut solo at Cape Town’s storied AVA Gallery.

Titled Ityala aliboli (an expression that loosely translates as “a debt that doesn’t wither away, rot or die”), the exhibition featured small, boxy things — sculptures, let’s agree — as well as works on paper.

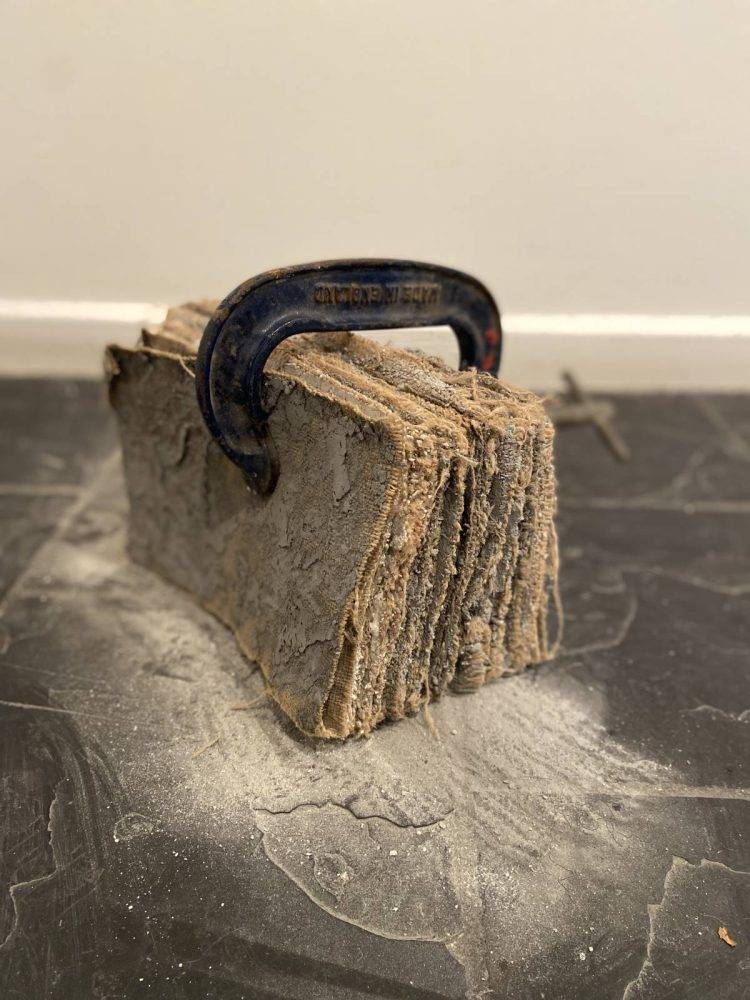

Standout pieces included the eccentric Proposition for Dis-order: Clamped Cement Sheets (2023), made from a dozen or so pieces of cement-stiffened hessian held together by an industrial G-clamp.

Displayed on the floor, it looked like a book, but also not. It was definitely curious and inexplicable, something to repeatedly look at rather than simply see once and get, and by getting, extinguish.

A serial collaborator, Nkomo is also a member of the band Dead Symbols with musician Fernando Damon and artist Rowan Smith. Imagine James Baldwin fronting an ambient synth band.

Nkomo’s AVA show included a kinetic sculpture made with Mitchell Gilbert Messina. Titled Proposition for Dis-order: 1 Cannon Ball in Motion (2024), the work featured a black cannonball on a plinth haltingly moving at intervals. It was pure analogue magic.

Surplus (and) People I & II (2024), also shown at AVA, comprised discarded scientific charts recording the distribution of Afrikaans onto which Nkomo overlaid black rectangles redolent of Russian avant-gardist Kazimir Malevich’s geometric Suprematist paintings and censors’ marks. As with the cannon-ball sculpture, Nkomo used shoe polish to achieve the dominant jet-black colour.

“I think of them as sketches or prototypes for much larger works,” stated Nkomo of the works on his AVA exhibition during an August walkabout. A month later, he opened his second solo, titled Proposition for Dis-order, at Cape Town’s TKH Gallery. The larger space enabled Nkomo to scale his ambitions.

Made with frequent collaborator Ndumi Mbala, Proposition for Dis-order: Playing Pétanque with Cannon Balls (2024) featured scientific maps of Afrikaans usage and word morphologies collaged to form a playing surface for a game of boule.

Flanking the rectangular playing surface was a slight brick plinth stacked with blackened cannon balls and a potted snake vine, a climbing plant endemic to Australia.

Most of the sculptural pieces in Nkomo’s second solo retained the modest scale and floor-based position of his first exhibition. A Pile of Time: Salt Cubes (2024) comprises square salt blocks assembled into a bunker-like form.

Nkomo’s interest in salt and salt solutions derives from his research into the wreck of São José Paquete d’Africa, a Portuguese slaver ship, bound from Brazil, that sank off Cape Town in 1794. Half the slaves drowned and many of those who survived entered bondage in the city.

Parsing this event, Nkomo found a subject that has enabled him to elliptically explore Cape Town’s history of racial slavery. The traffic of human cargo for profit also alerted him to the importance of debt, risk and time. Risk is a fertile notion in Nkomo’s work.

“The salt solution is so undisciplined and mobile,” said Nkomo of one of his key working materials at his AVA walkabout. “It spreads and becomes multiple things. It allows for this deep engagement with time, money, risk management.”

Nkomo’s practice slots into a lineage of austere, non-referential sculpture freighted with social implications. His method of using everyday things — shoe polish and salt — to create propositional statements links him to contemporary artists like Langa, Igshaan Adams, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Nicholas Hlobo and Kemang wa Lehulere.

But his work more immediately recalls ancestors like Michael Goldberg and Lucas Seage. Owned by the Wits Art Museum, Seage’s startling Coffin of the Migrant Worker (1983) comprises a wooden kist topped with two bundles of bones and charred sticks. It is the Rosetta Stone of a dissident strand in South African sculpture that I’m trying to flag here; work that refuses the corporate lobby or wine estate.

At his walkabout, Nkomo declined to speak about any specific works. His objects, while present and irrefutable, were also proxies for larger ideas to do with “black peoples’ place in the world” and ongoing racialised violence, he offered.

Dennis, whose solo exhibition Understudies recently opened at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (MOCAA), is similarly ambiguous about valorising and over-burdening their works with polite art-speak.

“Interested in the fraught history of scientific representation and intervention, the artist encourages us to think of artworks as models, diagrams, hypothetical annotations and simulations rather than sculptures, drawings and installations,” a statement in the handout for their exhibition reads.

This attitude extends to naming his vocation. Speaking at the opening, Dennis preferred “cultural worker” to “artist”. Jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim, speaking at the 1982 Culture and Resistance Conference in Botswana, did the same. Like Ibrahim, Johannesburg-based Dennis also does a lot of international touring.

Last year, Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland presented an exhibition focusing on his work with collective NTU (“an agency concerned with the spiritual futures of technology”) that Dennis cofounded in Johannesburg with Tabita Rezaire and Bogosi Sekhukhuni.

This year, they produced an impressive mural on an exterior wall of the Kunsthalle Basel, also in Switzerland. Informed by their discussions with physicists, geographers and writers, it included graphic lines and sentence fragments exploring “relational structures and historical conditions” that produced various “cycles of violence, extraction and ruination”.

Dennis characterised their mural as “a form of collective thinking enacted publicly and yet impermeable to conventional methods of public reading”. It is a fair elaboration of their practice more generally.

In 2013, then still sporting short dreadlocks, I watched Dennis write out the words of the Natives Land Act of 1913 in charcoal on a wall inside Cape Town’s old City Hall. A sentence in red bleeding into the legislation quoted a statement from Sol Plaatje’s 1916 Native Life in South Africa.

The earliest works in Dennis’s Zeitz MOCAA survey postdate this ephemeral mural. But land, or more pointedly landlessness, resonates in the earliest works on view, from 2016. These works are presented together with Model for a Gasp (Veiled), done this year.

It comprises a large black orb installed in a darkened nook near one of the exhibition’s two entry points. Made of a silky fabric and covered with a woven net threaded with cowrie shells like a skullcap, the sculpture periodically takes in air and inflates to a greater size. The sculpture breathes.

Dennis’s sculpture is at once captivating and cryptic. It is also impermeable to conventional methods of public reading.

It demands time, repeat visits, without the knowledge or promise that it will declare itself.

Art, to misquote Vives, is not a thing, nor entertainment, but a process of transformation — at least for those willing to volunteer their attention.

What's Your Reaction?